As of April 1, Making Stories is closed. Thank you for your support all these years!

As of April 1, Making Stories is closed. Thank you for your support all these years!

Spinning Fiber

Notions & Gifts

Books, Magazines & Patterns

About Us

We're here to help you stitch sustainability into every aspect of your making.

With our carefully curated selection of non-superwash, plastic-free yarns and notions, we have everything you need to get started on your next project - and the one after that.

Here's to a wardrobe of knits we love and want to wear for years to come!

We're here to help you stitch sustainability into every aspect of your making.

With our carefully curated selection of non-superwash, plastic-free yarns and notions, we have everything you need to get started on your next project - and the one after that.

Here's to a wardrobe of knits we love and want to wear for years to come!

Our Sustainability Pledge

Our Blog

Our Podcast

The Making Stories Collective

Fibre Reactive Dyeing & Sustainability - An Interview with Marina Skua

December 02, 2020 8 min read 1 Comment

Last week we heard from Jule at woollentwine about the complex relationship between natural dyeing and sustainability, and I'm so happy that we're back this week with one of my all-time favorite dyers, Marina Skua, to explore the world of fibre reactive dyes! Marina uses this specific type of dye in a carefully crafted process to make her dyeing as sustainable as possible and she opened up the dye studio door for a glimpse of how exactly she does that for us. She also shares her insight into how natural and synthetic dyeing compare in terms of sustainability - without further ado:

Welcome back to the Making Stories blog, Marina! I can't wait to chat about all things synthetic dyeing with you! Before we dive into that, could you tell us a little bit more about what it is that you do as a yarn dyer at Marina Skua?

Thanks, I'm so glad to be here! I source the fibres for my yarns from farms local to me in the South-West of England, and I hand-dye them in small batches at my home in Bath. While I do a very small amount of natural dyeing using plants from my garden and foraged locally, the majority of my colours are synthetically dyed. I mostly use fibre reactive dyes, rather than the more commonly used acid dyes, but the methods involved are very similar. I do use acid dye for colours that require the use of black, because it is impossible to get a decent black on protein fibres with fibre reactive dyes.

Last week we learned a lot about natural dyeing from Jule (woollentwine), and I'd love to start the same way we did back then - by exploring the process of synthetic dyeing. Could you define 'synthetic dyeing' for us and share which steps it encompasses?

This is a really broad question, so I'm going to narrow it down a bit. Whereas natural dyes are derived directly from specific plants or insects, synthetic dyes are manufactured through chemical processes.

There's a large range of different types of synthetic dyes, but the most common types you'll find being used by indie dyers are acid dyes and fibre reactive dyes. Acid dyes are formulated for use on protein fibres (wool, alpaca, silk etc.) as well as on nylon. They are so called because they require an acidic environment to bond with the fibre. Fibre reactive dyes are generally used for cellulose fibres, but can be used in an acidic process to dye protein fibres.

I'm going to talk about dyeing protein fibres, as that's what I dye most frequently, wool and alpaca. Dyeing methods can vary enormously depending on the dyer and the effect they're trying to achieve. I mostly use the immersion method, which is what I'll describe here. This is my process; other dyers will use variants on techniques and the order in which things are done.

I start with scoured (washed) yarn, generally I soak it in water before dyeing, but for some colourways it goes into the pot dry.

I use 30 litre stainless steel pots to dye in, and usually dye batches of 10 skeins (500 grammes). The dye bath needs to be mildly acidic for the dye to bind to the fibre. White vinegar works fine but really smells, so I use a citric acid solution, which is odourless and food-safe. I fill the pots with lukewarm water and add the dissolved citric acid.

Then I weigh out my dye powder on jewellers' scales, as tiny amounts are needed, then gradually add water, stirring to dissolve it. Once dissolved, the dye solution goes in the pot, followed by the yarn. The bath is then gently heated to a simmer for up to an hour, until all of the dye in the water has reacted with the yarn. There should be no colour left in the water‚ this is when the dye bath is 'exhausted' and you are left with dyed yarn and a pot of mildly acidic water. The yarn is then left to cool, gently rinsed and dried.

The combination of heat and acid in the dye bath makes the dye molecules form a covalent bond with the fibre. This means that the colour is really fast and won't be broken down by washing or sunlight, and won't be affected by changes in ph.

I'd love to learn a little more about the fibre reactive dyes! What are the main differences to acid dyes and why did you choose to use fibre reactive dyes?

There are actually quite a few different dyes in each group, with different composition and properties. The overall difference between the two groups is the kind of chemical bond the dye makes with the fibre. Fibre reactive dyes form a covalent bond, while acid dyes form a hydrogen bond, which isn't as strong. Fibre reactive dyes are more commonly used with cellulose fibres because they form that bond more easily than with protein fibres, but once that bond is made it's chemically stronger, resulting in a colour that is more fast.

The fibre reactive dyes I use are Procion MX dyes. It's a bit of chance that it ended up that way. When I first started dyeing yarn five years ago, it was just a fun little experiment that I did because I already had some Procion dyes in the house left over from doing some tie-dyeing on cotton a few years previously. After some research I found I could use them with a different method for wool.

I used these dyes for the first while, then when I started running out I ordered some acid dyes because I'd read they were the 'correct' dyes for protein fibres. As I worked with the acid dyes, I found the colour more difficult to control and give me the result I wanted. Different dyes 'strike' at different rates. The strike point is the moment the dye bonds with the fibre. For an even, solid colour, the dye should strike slowly, so the dye has a chance to reach all the fibres evenly before they start bonding. For speckles you want a really fast strike rate, the dye needs to bond with the fibre the second it hits, so the colour doesn't bleed. Because acid dyes form a chemical bond more easily with protein fibres, they generally strike faster. A lot of dyers who specialise in speckles and high-contrast variegation will use acid dyes for this reason.

I mix a lot of my colours myself, which gives really nice layers of hues in some colourways, and I found that my methods and desired results lined up better with the fibre reactive dyes I had been using to start with.

How would you describe the relationship between the different dye steps - and synthetic dyeing in general - and sustainability?

I think, again, the impact of the dye process depends a lot on the dyer. I've worked on my processes for a long time now to streamline everything, making it as efficient as possible on a small scale whilst working towards the best result.

I reuse the water I use to dye up to three times, which reduces the amount of water as well as citric acid I use. I use the water left over from soaking the yarn to rinse wool socks (as it often has some leftover detergent in it). I make sure I exhaust all of my dyes so that there's minimal dye going into the water system. Even then, our water treatment systems in the UK are designed to deal with much worse things going down the drain on a regular basis. All of my yarn is air-dried so no extra energy is used for drying.

So I believe that it is possible for an independent dyer to be careful about their practices and have very limited impact on the environment, that is what I aspire to.

Something curious I've observed over the past few years is that a lot of us knitters automatically seem to equate natural dyeing with sustainability, and synthetic dyeing, not so much. As you've worked with both, what's your perspective on why that is and what are some of the common misperceptions that we might have?

As with everything, there are layers upon layers to look into. I think a lot of it boils down to the 'natural = good, chemical = bad' fallacy. The word 'chemical' is rather useless here because everything is made of chemicals. This is why I prefer to use the term 'synthetic' to describe the dyes I use.

The mordants used to fix a lot of natural dyes are 'chemicals' (and range from harmless to seriously poisonous), and a lot of natural dyes and processes can be quite toxic. In the past the demand for natural dyes has endangered trees such as brazilwood, and many lichens that used to be abundant in Scotland are scarce now because of irresponsible gathering for dyeing wool for tweed.

From the point of view of the end user, naturally dyed items require special care and are more likely to fade. Many can change colour if washed at the wrong temperature or ph, and while this can be part of the magic, a lot of people prefer more reliable colours.

I don't mean to denigrate natural dyeing, I love dyeing with plants and am trying to increase the range of colours I can grow in my own garden, but the considerations are different.

In the meantime, the process for using synthetic dyes in the studio is a lot less resource intensive than natural dyes. It uses significantly less water and energy than natural dyes, and the resulting colour is more reliable, fast and easier to care for, which is likely to prolong the life of the finished item. I mostly focus on the broad and predictable range of colours I can achieve, with minimal consumption of resources, which will last for years under normal conditions without fading or changing colour.

Fundamentally I don't believe one method is categorically better than the other. Both have advantages and disadvantages and I think it's down to the dyer and consumer to decide which aspects to prioritise.

One aspect that I've come across when researching synthetic dyes is that they can contain hazardous chemicals which means both their production as well as their usage can be potentially dangerous, and safety measures for everyone who works with them are key. Can you tell us a little about the key safety measures when it comes to synthetic dyes, both in the production of the dyes and the usage of them?

The toxicity of synthetic dyes available to the public and used by indie dyers is generally not that high. There are indeed highly toxic dyes but these tend to only be used in larger-scale commercial production.

The fibre reactive dyes I use are considered safe as long as you're sensible, i.e. don't eat them. Any fibres dyed with these present zero risk to the consumer from a toxicity point of view. The dyes aren't absorbed at all by the skin (though unreacted dye will colour dead skin cells, which is why gloves are recommended for the dyer). Caution should be taken not to inhale the dye powder, which is only really an issue when mixing or speckling with dry powder. A small number of people experience an allergic reaction to fibre reactive dyes, but only when the powder is inhaled. Overall, the dye materials I use are less harmful than a lot of common household cleaning products, and used in much smaller quantities.

In terms of dye manufacturing processes, yes, it can be hazardous. The dyes I use are manufactured in Germany according to strict standards and regulations to ensure the safety of workers and to reduce the impact on the environment.

What are some of the tips you'd give a fellow synthetic dyer to make their practice as sustainable as it can be that they might not have yet heard of?

I'd mostly recommend consciously avoiding wastage of materials and resources. Choose methods that don't require single-use plastic (e.g. cling film for steaming), try to find a reputable local distributor for your dyes, and thoroughly research your dyes, ancillaries and methods to make sure you're working safely and efficiently.

Where can our readers find more about you and your work?

My website is www.marinaskua.com, and I have a YouTube channel where I talk about my dyeing and designs, as well as other projects with a sustainable focus. I also post regularly on Instagram as @marinaskua.

Thank you so much for sharing your knowledge with us, Marina! By the way - watching her podcast is one of my favorite pastimes while knitting. Highly recommend it!!

1 Response

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.

Also in Blog

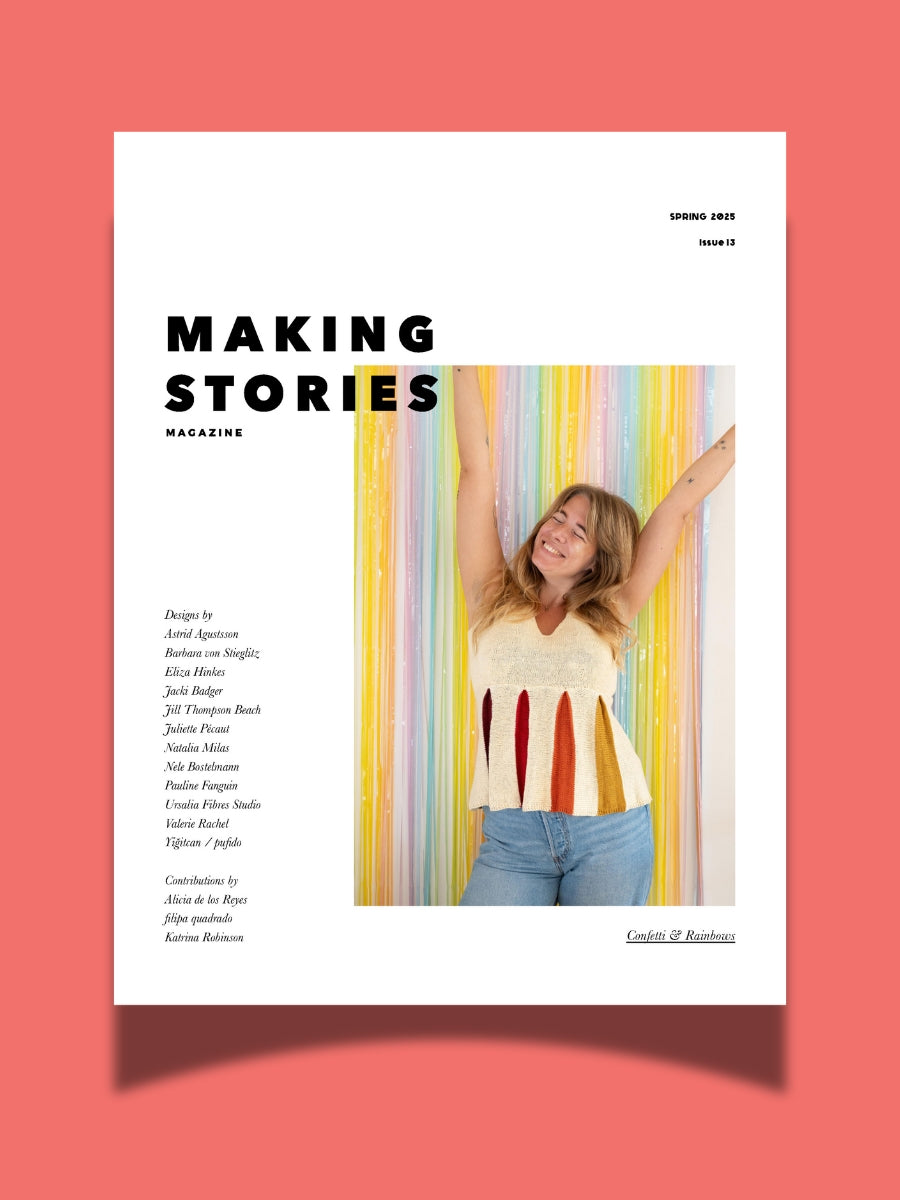

Issue 13 – Confetti & Rainbows | Official Pattern Preview

February 12, 2025 13 min read

Hi lovelies! The sun is out here in Berlin, and what better day to talk about one of the most joyful issues we've ever done than a brilliant sunny winter day – meet Issue 13, Confetti & Rainbows!

In Issue 13 – our Spring 2025 Issue – we want to play! Confetti and rainbows, unusually and unconventionally interpreted in 12 new knitwear designs – a journey through color, shapes, texture and materials.

Confetti made out of dried flowers, collected over months from bouquets and the road side. Sparkly rainbows, light reflecting. Gentle textures and shapes, echoing the different forms confetti can take. An unexpected rainbow around the corner, on a brick wall, painted in broad strokes.

New Look, Same Heart: The Story Behind Our Delightful Rebrand

January 16, 2025 4 min read 1 Comment

Hi lovelies! I am back today with a wonderful behind-the-scenes interview with Caroline Frett, a super talented illustrator from Berlin, who is the heart and and hands behind the new look we've been sporting for a little while.

Caro also has a shop for her delightfully cheeky and (sometimes brutally) honest T-Shirts, postcards, and mugs. (I am particularly fond of this T-Shirt and this postcard!)

I am so excited Caro agreed to an interview to share her thoughts and work process, and what she especially loves about our rebrand!

Thoughts on closing down a knitting magazine

November 19, 2024 12 min read 1 Comment

Who Is Making Stories?

We're a delightfully tiny team dedicated to all things sustainability in knitting. With our online shop filled with responsibly produced yarns, notions and patterns we're here to help you create a wardrobe filled with knits you'll love and wear for years to come.

Are you part of the flock yet?

Sign up to our weekly newsletter to get the latest yarn news and pattern inspiration!

shweta

March 12, 2022

Nice information you have provided. thank you

http://www.jagson.com/