As of April 1, Making Stories is closed. Thank you for your support all these years!

As of April 1, Making Stories is closed. Thank you for your support all these years!

Spinning Fiber

Notions & Gifts

Books, Magazines & Patterns

About Us

We're here to help you stitch sustainability into every aspect of your making.

With our carefully curated selection of non-superwash, plastic-free yarns and notions, we have everything you need to get started on your next project - and the one after that.

Here's to a wardrobe of knits we love and want to wear for years to come!

We're here to help you stitch sustainability into every aspect of your making.

With our carefully curated selection of non-superwash, plastic-free yarns and notions, we have everything you need to get started on your next project - and the one after that.

Here's to a wardrobe of knits we love and want to wear for years to come!

Our Sustainability Pledge

Our Blog

Our Podcast

The Making Stories Collective

Breed-specific yarn with Pam Allen

December 03, 2020 10 min read

Hello folks! Welcome to today's very special blog post. A little while back, you may remember that we wrote this post on Breed Specific yarn. Here at Making Stories, we love breed-specific yarn, so much so that we've been dying to get a little more 'specific' ourselves. While that original post gave a great overview of what breed-specific yarn is, we thought it would be fun to get into the very fibres of the topic. And that is where I am excited to welcome the fabulous Pam Allen to the blog.

Pam has worked in the knitting industry for many years as an independent hand-knitwear designer, editor-in-chief of Interweave Knits magazine, and as creative director at Quince & Co. She is the author of numerable books filled with stunning designs, and her latest venture is just as exciting as you would expect.

Stone Wool Yarns began back in 2014 in collaboration with Whitney Hayward and was built on a passion for breed-specific yarns. The more Pam learned about this topic, the more she fell in love, which seems to be true of most people (spoiler; it's because breed-specific yarns are awesome!). When she reached out to us to offer to share her thoughts on this subject and the creative journey of their latest yarn (Gulf Coast Native), we jumped at the chance to hear more.

What started as a simple, 'I'll send some questions, and you send the answers back' situation, evolved into a super generous and thoughtful essay of one woman's journey into the discovery of breed-specific yarns. What I love about Pam's writing is it illustrates that you can live and work in the fibre community for many years, but there are always new and exciting things to discover that make you fall in love with the craft all over again and that you are never done learning.

So without further ado, let me hand you over to the fantastic, Pam Allen.

Thanks so much, Claire and Hanna, for the opportunity to talk about my love (not too strong a word) for sheep breeds. I can't get enough of learning and talking about them.

Before I launch into your questions, I want to emphasize that I am not at all an expert on sheep breeds. I'm new to them and only recently learned about the myriad ways to think about sheep and their--and our--history. There will never be enough time to learn all that might be learned about the some1400 varieties (imagine!), but I have fallen into the sheep rabbit-hole and now I'm done for. Eat, sleep, breathe, etc.

When did you first become interested in breed-specific yarn?

The moment I tripped and fell was when we introduced Delaine Merino, a little over a year ago, and I volunteered to write up a blurb on the history and characteristics of this very specific regional sheep.

I contacted Deb Robson, co-author with Carol Ekarius of The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook (Storey Publishing, 2011), my go-to sheep book. Kind and generous person that Deb is, she read up on DM and got back to me. As she talked about the sheep's story, corny as it sounds, the veils lifted. For the moment, I wasn't thinking about sheep in knitting terms--fleece, yarn, knitted hand. Instead, I was seeing this particular breed as, well, having an identity. These specific merinos have, as all breeds do, a unique history. They, and all breeds, are a visual representation of Time. Sheep, in forms now long gone, were probably here before we were. The sheep who've evolved in pockets around the world are animals that differ in marked ways from each other--their fleece, size, and behaviors a response to the natural world--and, of course, to us--through time.

So that's my breed-interest origin story. I've since come to appreciate specific breeds and their vital importance for other reasons.

First, individual breeds represent all important diversity. In a world with so many people, wool production, like food, has focused on homogenizing fleece. Manufacturers of mass goods don't like to deal with variation. We want predictable results. So, sheep are often bred in the agribusiness way, categorized not by individual breed, i.e. history, but by desirable traits, e.g. whiteness, softness, crimp, and length of fiber. Distinctive breeds which have evolved over eons in response to a specific environment, bearers of unique and irreplaceable genes, are slowly disappearing or becoming artifacts on isolated farms. With homogenization we lose the great diversity of genes that make for resilience and hardiness, a loss we may come to regret, not just because we're left with bland white-bread herds, but because without genetic variety, sheep are more vulnerable to diseases, to potentially lethal viruses, a threat we can very much relate to these days. Preserving genetic diversity is the best failsafe plan.

Breeds interest me, as well, because we've grown up together. They bedded down with us when we lived in caves, so important were they to our earliest ancestors. Thousands and thousands of years later, the Egyptians carved their likeness into stone. Their fleece was revered by Spanish kings, so much so that when the sheep migrated with the seasons, they were afforded the right of way through towns en route. When early explorers came to the New World, they brought sheep with them by the hundreds--a 15th century convenience store: Meat, milk, and fiber. In fact, the sheep that traveled from Spain with the earliest explorers are probably the forbearers of the Gulf Coast Native.

Finally--and this one is close to my heart--breeds evolved (and still are evolving, of course) to be the specific animals they are because of eon-long relationships with their specific habitat. Like many of Nature's sometimes invisible connecting webs, sheep have been key in other animals' survival and adaptation. In Wales, for example, the Red-billed Chough and sheep have formed a symbiotic relationship. The sheep keep the grass short making it easy for Choughs to find insect prey and, still hungry, the birds eat pesky ticks from the sheep. In breeding season, they line their nests with wool. Mutually beneficial.

The yarns at Quince & Co have always felt like a celebration of natural fibre, what made you decide to go a step further to produce breed-specific yarns under Stone Wool?

Wool in and of itself is a wonderful thing--insulating, absorbent, elastic. And we're especially accustomed to celebrating softness in wool when we find it.

Breeds offer another way of looking at wool, as I mentioned above, a lens that captures history and relationship, variety and individuality. Considering breeds means looking not only at an animal's wooly traits, what the fleece is like for weaving or knitting, it means thinking about the animal in a larger context, understanding how the animal fits into a time and place. Breeds have stories, and if you like stories, as I do, then these animals offer a bonus over their lovely yarn, they offer the intrigue of their histories. Do I wax romantic?

Yes, I do.

My hope is that Stone Wool, like the other special breed companies, will alert knitters to the wonderful buffet of different kinds of wool, and also to the dwindling number of sheep from which these wools come.

Your new base, Gulf Coast Native, sounds so exciting! I know creating a new yarn is a pretty involved operation, but could you give us a little insight into creating this new base?

I'd read about Gulf Coast Native in The Sourcebook, and it seemed a good candidate for a limited edition. I contacted every name on the GCN sheep association website, and I think every single person I wrote to got back to me, even if it was to say they had only seven sheep and therefore couldn't help me. But several responses pointed me to the GNC grapevine and eventually I connected with Joanne Maki and her herd of 46 or so sheep. With the help of Mary Jeanne Packer, owner of a small commercial mill in upstate New York, a woman experienced in sourcing wool from small farmers, we got Joanne's fiber to the mill. Once there, it was sorted, scoured, drafted, and spun into two versions, a 2- and a 3-ply, because it was impossible to choose between them.

At the risk of gushing, let me say that I tend to get emotional when I open a box with breed-yarn samples. To pick up one of these skeins, sniff its irresistible smell of lanolin and whiff of machine oil, to squeeze it, to study its creamy color, to sense in the skein an ineffable waft of history, of origins--well, it's a slightly momentous experience.

I'll be honest, Gulf Coast Native is not a sheep breed I have ever heard about! Could you tell us a little more about this wonderful breed and why you chose it for your next release?

GCN seemed like a good choice for a couple of reasons, not the least of which is that few people, certainly not me, have ever heard of it. How better to highlight sheep variety than to choose a breed as rare as GCN?

Also, GCN are an example of a sheep whose origin is the polar opposite of that of our first limited edition breed, California Red (another wonderful yarn). CR was a deliberate 1970s cross of American Tunis and a hair sheep, Barbados Blackbelly, in order to develop a good meat animal with no annoying fleece to contend with. Happily, in terms of its desired outcome, the cross was a failure. California Red has a beautiful soft and luscious cinnamon-tinted fleece.

But I digress.

GCN, by contrast, is a mongrel, or landrace, sheep. Though it's hard to say for sure, it probably descended from Spanish Churro migrating north from Florida, later mixed with sheep the French brought to Louisiana and the Mississippi Delta, and even later bred as a ‘native' (its name to new arrivals) with traditional British breeds brought south by early Virginia settlers. Its gene pool is large and varied which results in sheep that aren't uniform. They're small but come in different colors, some have horns, some not. They're extraordinarily hardy. They learned to fend for themselves, foraging in woods as well as fields, surviving on a wide array of flora, including, happily, the invasive kudzu. They're great mothers, giving birth easily and attending carefully to their offspring.

Interesting note: The Gulf Coast Native Association is in the midst of coming up with criteria for identifying a true GCN. Joanne Maki mentioned to me the difficulty in creating the criteria. Unlike some sheep who can be measured by fleece fineness, ear position, wool on face, etc., GCN are perhaps identified as much by qualities that are trickier to pin down, e.g. hardiness and good mothering ability. Joanne is breeding for fiber, and as she does so, she keeps an eye out for the behavioral characteristics that so represent this particular sheep.

I know the last base you launched sold out during pre-orders, which is fantastic! Do you feel makers are more interested in using breed-specific yarns now more than, say, five/ten years ago?

I very much hope they are! I think (hope) that, in general, we're becoming more interested and concerned about our agricultural history. We look for heirloom seeds and apple varieties. Sheep are a part of that history, our history. I think we're becoming more aware of the rich world of specific breeds, these myriad types--think of colors in a garden, varying birds in trees--threatened by commercialization. Who wouldn't get excited by this humble and oh so various little animal. We mourn the regular loss of species in the wild, but traditional livestock are at risk as well.

I know if someone hasn't worked with breed-specific yarns before they tend to be a little hesitant. These yarns can certainly feel a lot different than the Merino or synthetic bases that dominate the yarn industry. What would be your advice to anyone who wanted to try something different?

Such a good question! First, I'd say, Fear not. We won't offer a scratchy yarn without telling you up front what to expect. And probably we wouldn't spin a scratchy yarn in the first place. We want to please. That said, these yarns might not be as soft as what we've come to value (perhaps to our loss), but they have other characteristics that make them worthy. Having just worked up two simple, one-skein hats to offer with a purchase of a skein of GNC, I can personally attest to its pleasure in the knitting. I worked cable patterns in the hats and marveled at how perfect the yarn, in both ply structures, looked in Aran patterns. Also, the fleece is the most beautiful shade of rich buttery cream. I've found that working with these different breeds has made me more appreciative of the many shades of white. The undyed naturals from various breeds could form a palette in themselves.

Is there anything else you would like to share with us?

Most of us now live in urban areas. Sheep live elsewhere. We experience wool on the hangar in a store, or if we're lucky enough to be knitters, we work with it as yarn. But since I discovered breeds, when I pick up my knitting, I don't think ‘wool.' Instead, I think Cormo or Cheviot. And I have a story in mind. I want to spread the word about these wonderful animals, to broadcast the importance of preserving their many kinds.

AND I want to once more thank the women who have gotten me this far. I'm grateful to Deb Robson. Anyone interested in learning more about sheep breeds would be wise to turn to The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook and to her excellent free class, Know Your Wool, on Craftsy, https://www.craftsy.com/post/know-your-wool/.

Good yarn is only partly dependent on good fiber. From my first phone call, Mary Jeanne Packer has guided the process. She has spent hours on the phone with me explaining conversion rates and everything else one needs to know when making yarn from a bag of raw fleece.

I'm grateful to these women whose generosity and kindness have gotten our Stone Wool Limited Edition Rare and Unusual Breed Yarn off the ground.

Where can we find out more about Stone Wool Yarns and Gulf Coast Native?

Please visit our website and sign up for our e-letter. We'll be putting the word out just as soon as we're ready to launch GCN. We have other limited editions lined up, so stay in touch. On our website, you can see our permanent specific breed offerings: Cormo (soft!). Corriedale, Cheviot, Romney Merino, and Delaine Merino (soft!). And you can always reach me at pam@thestonewool.co.

A huge thank you once again to Pam for sharing her wonderful words with us!

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.

Also in Blog

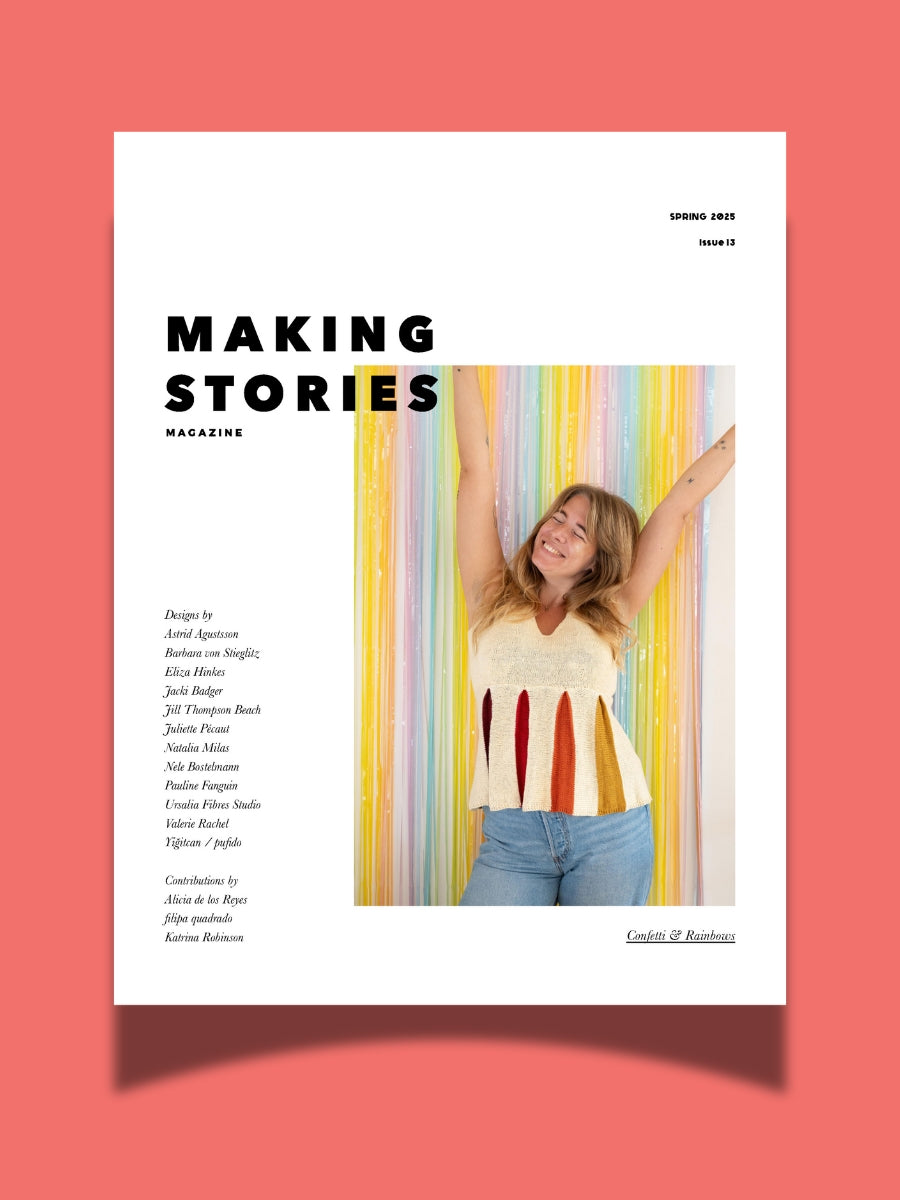

Issue 13 – Confetti & Rainbows | Official Pattern Preview

February 12, 2025 13 min read

Hi lovelies! The sun is out here in Berlin, and what better day to talk about one of the most joyful issues we've ever done than a brilliant sunny winter day – meet Issue 13, Confetti & Rainbows!

In Issue 13 – our Spring 2025 Issue – we want to play! Confetti and rainbows, unusually and unconventionally interpreted in 12 new knitwear designs – a journey through color, shapes, texture and materials.

Confetti made out of dried flowers, collected over months from bouquets and the road side. Sparkly rainbows, light reflecting. Gentle textures and shapes, echoing the different forms confetti can take. An unexpected rainbow around the corner, on a brick wall, painted in broad strokes.

New Look, Same Heart: The Story Behind Our Delightful Rebrand

January 16, 2025 4 min read 1 Comment

Hi lovelies! I am back today with a wonderful behind-the-scenes interview with Caroline Frett, a super talented illustrator from Berlin, who is the heart and and hands behind the new look we've been sporting for a little while.

Caro also has a shop for her delightfully cheeky and (sometimes brutally) honest T-Shirts, postcards, and mugs. (I am particularly fond of this T-Shirt and this postcard!)

I am so excited Caro agreed to an interview to share her thoughts and work process, and what she especially loves about our rebrand!

Thoughts on closing down a knitting magazine

November 19, 2024 12 min read 1 Comment

Who Is Making Stories?

We're a delightfully tiny team dedicated to all things sustainability in knitting. With our online shop filled with responsibly produced yarns, notions and patterns we're here to help you create a wardrobe filled with knits you'll love and wear for years to come.

Are you part of the flock yet?

Sign up to our weekly newsletter to get the latest yarn news and pattern inspiration!